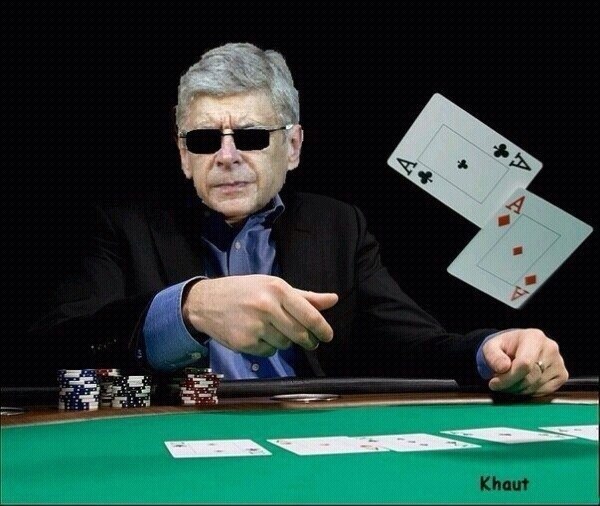

Back in the summer of 2012, Alex Ferguson paid Arsène Wenger the highest of tributes in claiming that the Frenchman could run a poker school in his native Govan after experiencing his haggling tactics over the transfer of Robin Van Persie that summer. It’s a compliment that might not have been appreciated by many Arsenal fans after witnessing the trauma a third big name exit from N5 in successive seasons. Wenger remarked that only time would tell who got the best out of that very deal.

A Brief Arsene Wenger History

Wenger was forced to admit that he knew he was effectively selling Man United the title and that’s exactly how the 2012/13 season panned out.

Many Arsenal fans, however, noted that for the £24 million which flowed into Arsenal’s coffers, Robin Van Persie only really gave Man United one good season. Many United fans may well retort that his sole season of Old Trafford excellence brought one title more than that which Arsenal have achieved since 2012.

Just who got the better deal out of that particular transfer may well be a moot point, but the bigger picture is of course is to concentrate on whether Arsenal have been well served by the Arsène Wenger school of transfer poker over his twenty one years at the helm. First, however, would be to look over what culture the Frenchman was walking into on arrival at Highbury.

This Highbury Years

In the years before 1996, Highbury was a place that, since the transfers of Irish duo Liam Brady and Frank Stapleton at the start of the 1980s, had never really lost big name players at the peak of their powers that Arsenal would otherwise have wanted to keep hold of. At the same time, Highbury was also a place which bagged the big name transfers in the first place.

The biggest name to come through the marble halls during the 1980s had been Charlie Nicholas, who came in from Celtic after finishing the 1982/83 season the as top scorer north of the border and bagging 48 goals in 74 games for The Celts, seeing off bids from FA Cup winners Man United and league champions Liverpool in the process.

“Charlie Nick” was overwhelmingly a North Bank hero during the mid to late eighties, and bagged two goals at Wembley against Liverpool in the 1987 League Cup final to end Arsenal’s eight-year trophy drought. Despite this, he underwhelmed on the pitch and ultimately never hit it off with incoming boss George Graham, who sold him off to Aberdeen in January 1988.

On the George Graham Years

Graham was famously never one to indulge the ‘big star’ mentality, as seen a decade later with David Ginola, whom he inherited at Spurs and also unceremoniously disposed of to Aston Villa. Star name signings were never really the thing at Highbury during his time. Both Alan Smith and David Seaman were fairly sought-after within top tier English football at the time of their arrivals, but Graham’s tenure was more notable for what big names were missed out on, such as John Barnes, Peter Beardsley, Ray Houghton, Tony Cottee, Alan Shearer and Roy Keane.

Arsenal were very much in the hunt for those players back in the day, but an unwillingness to pay over the odds or break the Highbury pay structure meant that they were instead snapped up by other First Division rivals. Graham’s success instead was built upon a fruitful youth system which he inherited from his predecessor, Don Howe, and shrewd lower division signings such as Lee Dixon and Steve Bould. By 1995, the transfer structure was seen as rewarding mediocre, but loyal players from a less fruitful youth set up at Highbury less than ten years prior; especially so after the Premiership began to attract big name foreign players such as Jurgen Klinsmann at Spurs.

David Dein’s Involvement

Graham’s exit in 1995 saw a break in transfer policy at Highbury, firstly in that David Dein became heavily involved in transfer negotiations. Previously, Graham had ‘always told David that I preferred to work alone’. Four months on, his exit saw a trebling of Arsenal’s transfer record, with the signing of Dennis Bergkamp from Inter Milan. Bergkamp’s signing shattered the existing pay structure by making the Dutch master the highest-paid player in the English game at the time.

The new approach at Highbury was underlined further when within a month Arsenal splashed a further £7 million on David Platt’s from Sampdoria, beating both Man United and Spurs to his signature. One year on, Dein brought in Arsène Wenger after the ousting of Bruce Rioch after just one season.

The Arrival of Arsène Wenger at Highbury

For the next five years, Arsenal did continue to make big-name signings of players who had Europe-wide notoriety at the time of their coming to Highbury, such as European Cup winner Marc Overmars from Ajax in 1997, Nwankwo Kanu from Inter Milan, World Cup winner Thierry Henry from Juventus, French Euro 2000 winners Syvain Wiltord and Robert Pires, Dutch international Giovanni Van Bronckhorst, as well as beating the like of Inter, Man United and Barcelona to the signature of Sol Campbell by making him the first player in England to earn a weekly six figure income. In contrast, Wenger also brought in former Monaco youth products Emmanuel Petit and Gilles Grimandi, previously unknown this side of the channel.

There was, however, also a game changer which also occurred around this time in the shape of the Bosman ruling, laid down by the European Court of Justice in 1995. Players were now permitted to move on a free transfer on the expiry of their contract.

Previously, a player could only move for free if his club failed to renew his contract on terms no less advantageous to the player than his previous one. If his existing club offered a new contract at least as rewarding as the last, it could still demand a compensation fee in return for his departure.

The ruling also abolished existing rules which limited the number of non-indigenous players as a restraint of trade. Arsenal reaped the benefit of this with the transfers of Marc Overmars (from the break-up of Ajax’s mostly home grown Champions League winning side) and Sol Campbell (Spurs being powerless to prevent their captain crossing the Seven Sisters Road divide).

Economics 101

Arsène Wenger also came to the job with a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Strasbourg and arguably had a more methodical approach to transfer dealings than most managers within the game. In ‘Inside Story’—the autobiography of former FA Chairman Greg Dyke—speaking on his time as a director at Man United, he had commented that the general ethos of how to make a small fortune out of football at the time was to ‘start with a large one’ and that:

‘Virtually no one – not the manager, the players, the staff of the club, and certainly not the fans – cares whether you make any money’.

Wenger’s transfer perspective differed somewhat in employing an economist’s perspective of players as assets which should appreciate in value, by buying them low and then selling them on high.

The first signing at Highbury made on his recommendation shortly before his arrival was Patrick Vieira for £3.5 million, under the noses of Ajax. Within a year there had also been the signing of Nicolas Anelka from Paris St. Germain for around £500,000, exploiting a loop-hole within the French transfer system.

The former was sold on to Juventus for £13.7 million nine years later, while the latter moved to Real Madrid for £22.3 Million in 1999. Anelka’s sale, however, marked a turning point with regard to Arsenal transfers.

Thirteen years prior, George Graham’s first transfer dealing was to sell an up-and-coming nineteen-year-old Martin Keown to relegation candidates Aston Villa for £250,000 for refusing to agree to the latter’s demand of a £50 per week pay increase. Graham later paid a figure ten times the price to bring Keown back to Highbury seven years later, but along with the exit of Stewart Robson—Arsenal Supporters Club player of the Year twelve months prior—for allegedly talking back to the manager, it laid down a marker to players that the management would not tolerate liberties being taken.

The Anelka saga reversed matters. Wenger had sold on Ian Wright to promote Anelka to the status of a guaranteed regular name on the first team sheet. Despite London being a couple pf hours via the Euro Tunnel from his native Paris, it was reported within the British Press that Anelka was ‘bored in London’ and that: ‘I don’t want to know anybody and don’t want to. I don’t think I’ll see my contract through’.

Anelka acquired the nickname of ‘the Incredible Sulk’, had ongoing issues with team-mate Marc Overmars as well as an overbearing influence from his brothers, Claude and Didier. In the summer of 1999, Anelka was shipped out to Real Madrid. Arsenal earned handsomely off the back of the transfer, but you get the feeling that Graham, who has stated he would never keep hold of a player who felt he was doing the club a favour playing for them, would have spotted Anelka’s personality defect earlier and shipped him out of Highbury a lot sooner.

The unwanted precedent which the saga created is elaborated by Jon Spurling in his 2003 publication ‘Rebels for the Cause’, which dedicates a whole chapter to it. Spurling states that:

‘Like Brady and Stapleton in the early 80s, he (Anelka) made us feel unhappy about ourselves….the Gunners regained the unwanted title of being a ‘selling club’. On the grand European stage, Arsenal were at the mercy of the wealthier La Liga Clubs’.

As will be seen in Part Two of this piece, pretty much every summer since (with a few exceptions) has been Groundhog Day with Arsenal embroiled in a struggle to retain its big star name players. The next chapter will be concentrating on just how well Arsène Wenger has played his hand to this situation in the years since.

Follow Me on Twitter@robert_exley

Main image credit: